Design as On-going Research vs. the One-off

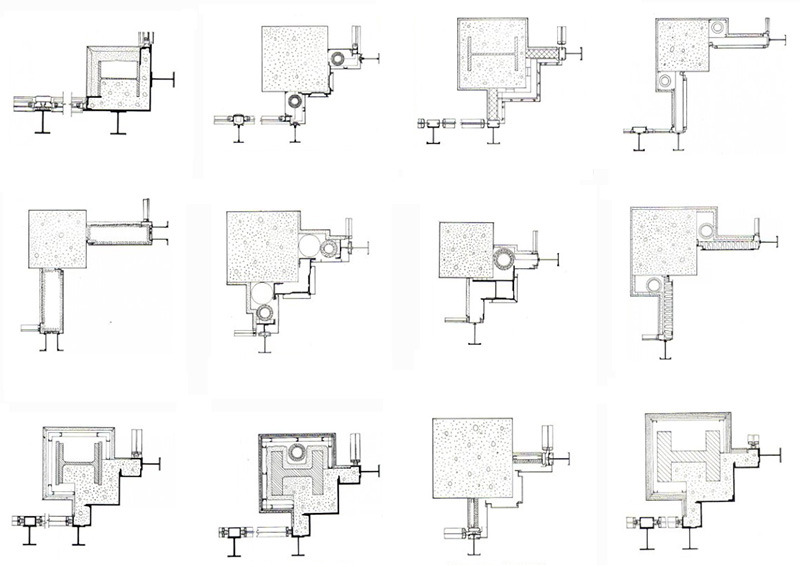

During a recent event at Utile where NADAAA and o,u/Utile teams shared their design submissions for a project in the Middle East, Nader Tehrani challenged the o,u/Utile team to include trans-project design research and preoccupations in future design proposals. Citing the design operations and features of a house in New Hampshire as one impetus for his team’s proposal, Tehrani made the case for disciplinary agendas that carry across multiple projects. Without stating it outright, Tehrani implied that such continuities in design agendas would result in richer and more meaningful proposals. While I favor self-conscious theorizing (while at the same time still meeting, if not exceeding, the client’s expectations), I am not sure that a practice that champions “evolving consistency” is the only model. Certainly, Mies van der Rohe’s post-war obsession with the corner of his glass and metal panel buildings is one exemplar of evolutionary architectonic thinking (Palladio’s villas are another). Mies’ multiple versions of the corner detail, provoked both by a larger conceptual agenda for each building and his growing interest in facades that suppressed the reading of the structural bay, have the same satisfying narrative arc and denouement as the sequence of prehistoric proto-horse fossils at Harvard’s Peabody Natural History Museum.

Diagrams by John Winter, The Architectural Review, February 1972

But if Mies is one kind of practice model, Eero Saarinen is another. In a very unlike-Mies way, Saarinen and his collaborators (which included, importantly, Kevin Roche), invented completely new organizational approaches and architectural languages for each new commission. And while each building partly borrowed from the work of other architects (Gordon Bunschaft and Mies – sort of – for the GM Technical Center, for example), they were each unique and fully-wrought technical, language, and symbol systems.

But if Mies is one kind of practice model, Eero Saarinen is another. In a very unlike-Mies way, Saarinen and his collaborators (which included, importantly, Kevin Roche), invented completely new organizational approaches and architectural languages for each new commission. And while each building partly borrowed from the work of other architects (Gordon Bunschaft and Mies – sort of – for the GM Technical Center, for example), they were each unique and fully-wrought technical, language, and symbol systems.

Eero Saarinen, GM Technical Center, Warren, Michigan, 1949-55

This eclectic approach, partly necessitated by the demands of corporate clients looking for uniquely imageable buildings, required a way of thinking that was radically opposed to Mies. Rather than play out design preoccupations across multiple commissions, Saarinen and his team must have worked vigorously to come up with novel conceptual frameworks and building systems. Utile, I think, follows a middle ground by self-consciously applying lessons learned from recent projects (both pragmatic and architectonic) while finding new issues to spark fresh design thinking, whether because of the site or program. In the end, I suppose, it’s what all relatively mature architects do, whether they theorize about it or not. The larger lesson from Tehrani is to be more self-conscious about ongoing design preoccupations. William Saunders, the former editor of Harvard Design Magazine, once told me that a “theoretical architect” is nothing more than an architect that is intellectually self-aware about one’s ongoing work. -Tim

(Update: Nader Tehrani responds to Tim’s comments.)